At 3:58 pm, the workday begins to ease. Across Indian offices, hostel corridors, and apartment kitchens, the same ritual plays out: a phone screen goes dark, a mug appears, someone asks, “Chai loge?” A plate follows. For years, that plate was non-negotiable: samosa, bhujia, biscuit, something deep-fried and familiar.

Today, the plate is starting to look different. Roasted chana sits alongside kachori. Millet khakhra shares space with glucose biscuits. There’s a makhana mix labelled “peri-peri” or a small pack of “protein namkeen” someone got on Instamart. A bottle of “probiotic iced tea” quietly replaces the second cola.

The 4 pm break has not turned “healthy”. It has become contested.

The brands gaining ground in that ten-minute window share one thing: healthy wins India’s 4 pm only when it behaves like a habit — familiar, taste-first formats with functional benefits (maida-free noodles, probiotic teas, protein water), priced for impulse and wired into daily routines. For consumer investors like Rukam Capital, and for anyone trying to understand where the next compounding brands might emerge, that 4 pm slot is no longer a throwaway moment. It’s a stress test.

The numbers under the snack plate

The shift is not just anecdotal.

Farmley’s Healthy Snacking Report 2025, released at its Indian Healthy Snacking Summit, captures the new baseline: 94% of respondents say taste is still the top priority even when choosing healthy snacks, while 72% actively seek more nutritious options, and a majority now prefer preservative-free products.

If that data were plotted as a bar chart, taste would tower over everything else, but health would no longer be a thin line at the bottom. The visual would show two almost parallel bars, taste and health, suggesting not a trade-off but a merger.

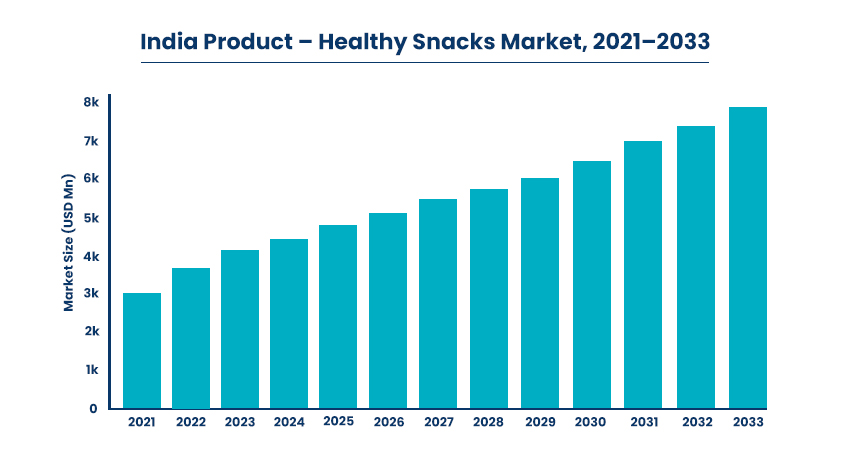

Underneath those preferences sits a large and growing market. IMARC estimates India’s healthy snacks market at about USD 3.13 billion in 2025, projected to reach USD 4.77 billion by 2034. The broader snacks market is even larger: around ₹46,571 crore in 2024, forecast to more than double to ₹1,01,811 crore by 2033.

Most of that consumption doesn’t happen at parties or cinemas. It happens in micro-breaks: between Zoom calls, outside tuition centres, at school gates, on local trains. The 4 pm slot is simply the most visible of these. It is regular, emotionally charged and socially shared, exactly the kind of setting where “better-for-you” can either become the default or remain an occasional experiment.

When “healthy” felt like homework

Today, snack aisles are gradually turning green and brown with millets, seeds, nuts, and roasted mixes, but this does not mean Indian consumers suddenly and easily embraced strict diets. In fact, the first serious wave of “diet” branding showed how fragile the shift can be when it fights existing habits.

Many early products spoke in a scolding register: “guilt-free”, “zero oil”, “diet snack”, “slimming mix”. They often arrived in unfamiliar formats with chalky textures or aggressive seasoning, priced far above the regular bhujia or biscuits stacked beside them.

The trial was easy to generate: a New Year’s resolution, an Instagram recommendation, a wellness trend. But repetition was hard. At 4 pm, after six hours of work or school, very few people want to negotiate with their food.

That tension is now visible in data beyond snacks. Multiple surveys and expert analyses suggest that around 70–73% of Indians are protein-deficient, and most are unaware of how much protein they actually need. Yet a large share of those same consumers still reach for deep-fried, carbohydrate-heavy comfort at snack time. Awareness alone doesn’t move a hand away from the samosa.

What moves it, slowly, is when the “better” option feels exactly like the thing it is replacing — just lighter, or more functional, or less punishing at 6 pm.

Healthy, disguised as a habit

Successful products follow a pattern.

The first part of the pattern is format. Maida-free or millet noodles that boil in two minutes and come with a masala sachet still respect the evening noodle ritual. Roasted sev and chana spill into the same katori that once held fried namkeen. Protein water or kombucha sits in the fridge door where cola used to live.

Nothing about the choreography changes: tear, pour, stir, share. The upgrade happens in the ingredient list and in how the body feels afterwards.

The second part is flavour. The Farmley report’s central insight is simple: Indians have become more demanding about nutrition, but flavour remains non-negotiable. A pack that leads with “Achari Chana” or “Peri-Peri Makhana” enters the conversation as food; a pack that leads with “Low GI Keto Mix” enters as a lecture.

Vinod, founder of Naturally Yours, reinforces this:

“Taste is paramount. It is the taste that you have to nail first. Unless and until you have nailed the taste, there is no habit changing. Even for our category, Maggi is so synonymous with taste and convenience. Hence, until and unless we are better or at least as good as them, it cannot change the customer’s habit of eating something healthy. Every category is going through this, and 5% to 7% of each category over the next 5 to 7 years will completely shift towards healthy eating, but they have to crack the taste first. Without that, the change is not going to come through.”

Put on a chart, “taste first, then health” would be the dominant preference across segments. That’s why the most interesting brands don’t shout about health on the front. They quietly print their case on the back.

The third part is the function. In a protein-deficient country, functional promises resonate — but only when they are easy to understand. Reuters’ reporting on India’s “protein craze” notes that high-protein dairy alone reached about USD 1.5 billion in 2024, with double-digit growth, and that mass brands from Amul to fast-food chains are leaning in with protein-enriched products for everyday use.

The SKUs that stick don’t offer a thesis. They offer sentences like “keeps you full till dinner”, “sits light during office hours”, “adds 10g protein to your day”. The frontline user at 4 pm is not counting macros; they are checking how they’ll feel at 7 pm.

Finally, there is flow, where and how the snack shows up. Quick-commerce baskets have turned afternoon cravings into one-tap decisions. Office pantries now decide what employees see when they get up from their desks. Tiffins have begun carrying roasted mixes and millet crackers alongside the idlis and parathas.

If all those touchpoints were drawn as a funnel, discovery would start in modern trade and D2C, while habit formation would happen quietly at home, in offices and in schools. The product that makes it into the “forever refill” list on an app, in a pantry, in a tiffin routine, effectively wins the 4 pm slot without shouting about it.

Nutrition: a live rehearsal for 4 pm

India’s growing interest in everyday nutrition is reshaping not just breakfast plates but the important 4 pm break. This is the moment when cravings rise, energy dips, and people look for something quick, light and comforting. Just like the shift toward healthier breakfasts, the 4 pm slot is changing as consumers move away from heavy namkeens, fried snacks and sugary biscuits toward options that refuel without slowing them down.

Across offices, colleges and homes, people are choosing nutritious and easy-to-eat mini snacks such as multigrain crackers, fox nuts, roasted chana, millet puffs, nut and seed mixes, Greek yogurt cups, protein bars, probiotic drinks and small fruit bowls. Even traditional choices like chivda, murmura, sprouts and homemade thepla rolls are being adapted into lighter and more convenient formats.

Pranav, founder of AWSUM, captures this mindset shift:

“I always believe that once you have more money at your disposal, you do not eat more, you eat better. I mean, that is the transition that happens.”

The 4 pm break is tracing a similar arc. Maida-free noodles, roasted makhana, baked savoury mixes and “smart” chaat kits are all, in their own way, light, nutritious upgrades that satisfy cravings while keeping energy steady. The common trend is convenience and comfort: products that feel familiar, digest easily, provide steady energy and do not lead to afternoon sluggishness.

Public health conversations around balanced portions and mindful eating are encouraging this shift. As a result, the 4 pm break is becoming a small moment of intentional nutrition. People want something tasty, light and good for them, and increasingly, they are finding it.

A ground-reality lens, not a Silicon Valley one

This is where investing philosophy and snack behaviour begin to rhyme.

On Daybreak, The Ken’s daily podcast, Archana Jahagirdar of Rukam Capital talks about why the “crazy genius founder” archetype doesn’t really fit Indian consumer reality. In that conversation, she emphasises patience, smaller but more deliberate bets, and a close reading of how Indian households actually live and spend, instead of importing Silicon Valley expectations of blitzscaling and hero narratives.

The 4 pm snack is a perfect example of why that lens matters. It is tempting to treat “healthy snacking” as a single, homogenous category where a global playbook can be applied: plant-based, low-carb, keto-friendly, influencer-driven. On the ground, the reality looks messier with instances where a schoolteacher in Indore wants something that doesn’t make her sleepy in class, a call-centre employee in Noida wants a snack that fits a ₹20 budget but doesn’t spike his sugar and a parent in Bengaluru wants a lunchbox filler that feels fun to the child but is, quietly, less junky.

Nitesh, CEO and Co-Founder of Blue Tea, explains the intersection of awareness and accessibility:

“Firstly, the most important factor is awareness, because most people do not know the outcome of the things they are consuming. Then comes the question of affordability. Many people wonder whether they can actually buy these products. Cost is an important factor, since only about 2 crore people in India can afford D2C brands, and we are all targeting them. So awareness has to increase, and costs have to come down, which will only happen with scale.”

Brands that ignore these specifics risk mistaking online conversation for market size. Those that pay attention to the mundane details of 4 pm, such as how much time there is to prepare something, what’s stocked in the office canteen, and whether the tiffin box has separate compartments, end up with very different product and distribution choices.

What 4 pm reveals, quietly

From afar, Indian snacking feels noisy and unpredictable with new flavours, flash discounts and micro-trends pulling attention in every direction. But zoom into the 4 pm window, and the signal becomes clear. This is where India quietly rehearses its shift from indulgence to “slightly better,” where taste still leads, and lighter upgrades slip into habit without fanfare.

For the media watching this space, 4 pm is a clean behavioural tell: which brands are moving from resolutions to routines, and how invisible “healthy” can become when it plays by taste.

For investors and founders, the same slot is an operational question. A healthy-snacking pitch deck can cover TAM, differentiation, and CAC; a 4 pm snack in someone’s hand is a daily referendum on whether that story checks out. And for the person actually holding the snack, the calculation is simpler: does this taste good, sit light, and cost about what today can bear?

The brands that answer “yes” to all three are already quietly winning India’s 4 pm. They don’t need to shout about being healthy. They just need to behave like a habit.

For those who want to understand this behaviour more deeply, this episode on the cultural psychology of India’s snacking habits is a worthwhile watch.

Watch here:

Is India Ready to Choose Healthy Over Junk? | Startup Table with AJ S02 EP19