Founders often discuss brand architecture early, especially when thinking about growth, extensions, or portfolios. What is discussed far less explicitly, however, is how deeply that choice shapes capital allocation over time. The decision between building a Branded House or a House of Brands is not merely about logos, naming, or marketing strategy; it is a structural choice that determines where focus lands, how capital is deployed, and how risk compounds across products and categories.

Brand architecture influences margins, working capital intensity, organisational complexity, and distribution efficiency. More importantly, it sets the ceiling on the kind of growth a consumer business can sustain and the types of exits it can realistically support. Seen through this lens, architecture is not a branding exercise; it is a long-term capital allocation decision. Understanding this early often makes the difference between building a coherent, scalable consumer platform and assembling a collection of disconnected products.

Compounding vs Diversifying Capital

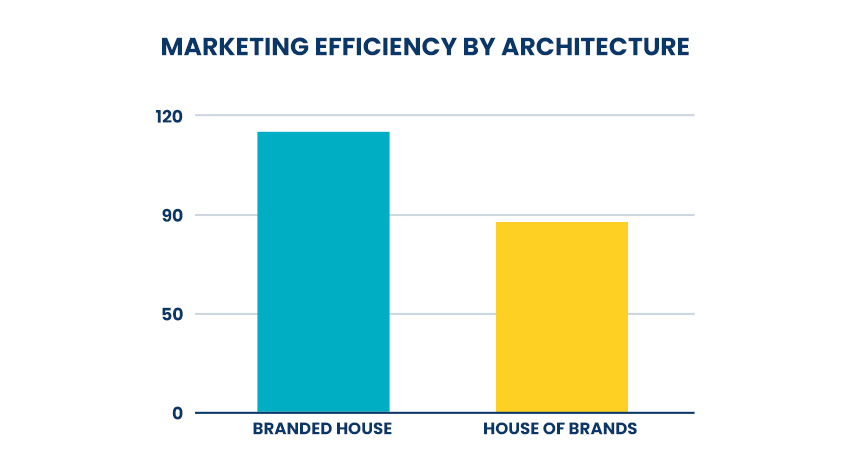

A Branded House concentrates equity in a single masterbrand. Marketing spends compound across launches; distribution benefits from a unified pull; and organisational focus remains tight. Apple is the textbook example; iPhone’s success reduces CAC for Apple Watch and services. Across categories, companies using a single master identity can see up to ~30% higher marketing efficiency, as trust transfers across products.

The power of compounding is clear: one successful product accelerates adoption for the next, operational complexity stays low, and brand equity grows cumulatively. But the model is not without limits. Unlike a House of Brands, a Branded House cannot target multiple distinct audiences with independent narratives, and one misstep, from quality to positioning, erodes the entire portfolio’s credibility. Scaling into unrelated categories under one brand can dilute perception, particularly when price or segment expectations diverge. Founders pursuing a Branded House are essentially betting on the durability of a single equity engine.

Independent Engines in a House of Brands

A House of Brands spreads risk and allows precision segmentation. Each brand operates as an independent growth engine, optimised for its segment, pricing, and category dynamics. Procter & Gamble’s Tide, Pampers, and Gillette are classic cases; consumers rarely associate them with P&G, yet the company benefits from isolated execution and modular financials.

This structure offers optionality: different strategies, margins, and consumer experiences can coexist without reputational spillover. But it comes at a cost. Unlike a Branded House, a House of Brands cannot leverage a single brand’s equity to reduce CAC or accelerate adoption across categories, meaning marketing spend, distribution effort, and operational complexity are higher. Each brand must earn awareness independently, and working capital intensity grows with portfolio size.

Trent Limited, part of the Tata Group, illustrates this strategy clearly in India. While Westside and Zudio both sit within the Tata–Trent ecosystem, each operates as an independent growth engine, optimised for different segments and pricing models. Westside is a mid-premium fashion and lifestyle brand built on private labels and margin discipline, while Zudio is a high-velocity value-fashion engine designed for aggressive pricing, rapid store rollout, and fast inventory turns. By keeping the brands distinct, Trent avoids pricing conflict and perception dilution. Zudio’s rapid rise to over ₹7,000 crore in under a decade, alongside Westside’s steady, margin-led growth, highlights how separate engines can deliver very different capital outcomes within the same group.

In emerging markets like India, where consumer segments and category nuances are sharp, the House of Brands is particularly effective for portfolios spanning both mass and premium segments, or culturally differentiated offerings.

Operational and Margin Implications

Architecture directly affects unit economics. Branded Houses achieve lower CAC, shared operational overheads, and greater working capital efficiency through consolidated supply chains and forecasting. A single brand can negotiate shelf space and distribution leverage more effectively, enhancing gross margins.

House of Brands allows segment-specific margin optimisation. Premium sub-brands can run high-margin, low-volume strategies, while value brands chase scale. But this modularity comes at a higher marketing spend and operational overhead. Founders must weigh incremental cost vs incremental optionality, a decision that scales disproportionately as the business moves from Seed to Series A.

Distribution and Growth Trade-offs

Distribution behaves differently under each model. Branded Houses leverage cumulative pull, accelerating shelf adoption and reducing negotiation cycles for new SKUs. House of Brands requires negotiation and visibility for each brand individually. Still, it allows channel-specific optimisation, for example, a premium beauty brand in lifestyle retail vs a value variant in modern trade channels.

Founders building in fragmented or competitive markets must ask: where will brand equity unlock faster penetration and lower friction, through unified strength or independent precision?

Category Dynamics and Consumer Signals: How Architecture Shapes Market Response

A less obvious but critical dimension of brand architecture is its interaction with consumer perception and category dynamics.

In a Branded House, the parent brand often dictates category framing. For example, L’Oréal Paris positions itself as a premium beauty authority; every skincare, haircare, or cosmetic launch benefits from this trust. Here, brand equity anchors the category conversation, making it easier for new products to gain attention and shelf space.

A House of Brands allows micro-positioning and faster adaptation. Take Hindustan Unilever’s portfolio: Dove can be premium personal care, Lux for indulgence, and Lifebuoy for functional hygiene. Each brand responds to unique consumer signals in its niche without being constrained by a master narrative. This approach helps founders experiment with product-market fit, price elasticity, and distribution strategies in parallel, particularly useful when consumer segments are heterogeneous.

Consumer data shows that house-of-brand portfolios often outperform in categories with high segmentation or evolving consumer tastes. In India, urban beauty and personal care segments have seen niche brands grow at 20–25% CAGR while mass masterbrands grow at 10–15%, illustrating the value of targeted brand strategies in emerging categories.

Exit Considerations and Investor Narrative

Architecture shapes the growth story investors can hold onto. Branded Houses deliver a cohesive, high-leverage narrative: one masterbrand, multiple revenue streams. They appeal to strategic acquirers and public markets that value simplicity and trust compounding.

House of Brands signals portfolio optionality and category flexibility. Financial buyers may value the independence of each brand, enabling modular monetisation or partial exits. The architecture choice thus dictates not only operating strategy but also exit potential and investor perception.

Hybrid and Endorsed Approaches

Most modern consumer businesses rarely stay purely at one end. Hybrid models, in which a masterbrand endorses independent sub-brands, allow efficiency without sacrificing segmentation precision. Endorsement transfers credibility and trust to sub-brands while keeping reputational risks compartmentalised. This approach is increasingly common in beauty, personal care, and FMCG portfolios targeting both mass and premium segments simultaneously.

Strategic Takeaways for Founders

Define your growth engine:

Is your ambition to compound a single trust narrative or diversify risk across independent engines? This choice determines whether growth is driven by cumulative brand pull or by parallel experimentation across categories.

Map capital deployment:

How much can each brand spend to earn equity before reaching scale? Branded Houses reward efficiency and patience, while House of Brands requires founders to underwrite higher upfront marketing and working capital per brand.

Assess operational complexity:

Can your teams manage multiple P&Ls, or should you optimise around one unified identity? Organisational maturity often dictates whether complexity becomes a lever or a source of friction.

Consider exit pathways:

Are strategic acquirers or financial buyers likely targets? Architecture shapes which story resonates, simplicity and scale versus optionality and modular value creation.

Test and evolve:

Hybrid structures often emerge when portfolios span unrelated categories or price tiers. The right architecture is rarely static; it evolves as capital availability, consumer signals, and category adjacency become clearer.

To conclude, House of Brands or Branded House is not a marketing decision; it’s a capital allocation framework. It determines how marketing, working capital, talent, and organisational focus compound over time. Every choice carries trade-offs between efficiency, risk, precision, and optionality.

In consumer businesses, the architecture chosen often reveals the future trajectory of growth, margins, and investor value, long before numbers do. Founders who consciously align architecture with capital, audience, and category dynamics set the stage for durable, scalable, and investable businesses.