Most founders start by asking a simple question: Who is my customer?

In Beauty & Personal Care, this question often misses the mark, not because the customer is hard to find, but because the ‘customer’ is rarely just one person making all the decisions.

The person using the product might not be the one paying for it. The one who pays might not be the one who chooses it. Sometimes, the person making the choice is not even present—it could be a friend sharing a Reel, a partner suggesting ‘try this,’ a salon professional giving advice, or a set of online reviews that make the decision feel safe.

This divide is happening more often because the category is changing. Beauty products are no longer bought just for a set routine, they are now chosen in response to real-life moments like workdays, sweating, weddings, stress, travel, or weather. These moments are often termed ‘Beauty Spaces’ such as ‘Work Mode,’ ‘Sweat & Reset,’ and ‘Evening Exhale,’ where people pick products for what they need right then, not for a perfect routine.

When you look at beauty this way, ‘who buys’ is no longer just about age or gender. It is about behaviour. This idea goes beyond beauty, too—any product used in private, discovered in public, and paid for by someone weighing the risks works the same way.

The Buyer Is a Unit, Not a Person

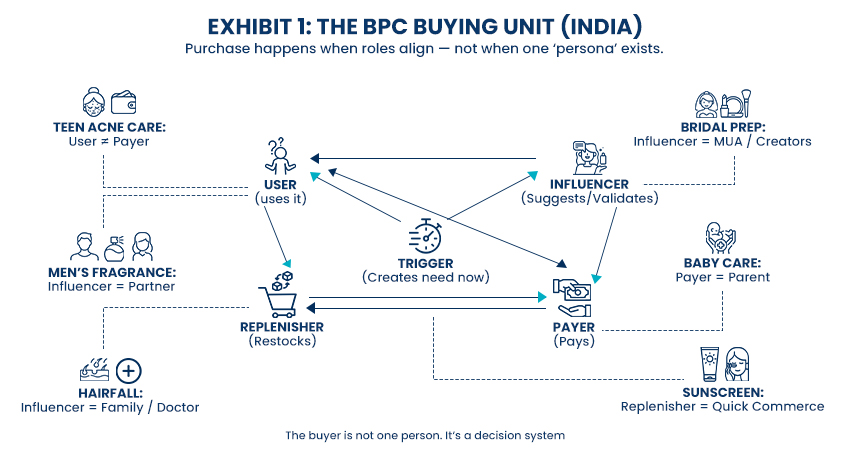

In India today, many beauty and personal care purchases are made by a small group making decisions together. This group, or ‘buying unit,’ usually includes five roles, though one person can play more than one role depending on the situation.

There is the user who actually uses the product. The trigger is the event that creates urgency, like a breakout, a wedding, humid weather, or a long commute. The influencer is the person who helps validate the choice; this could be a creator, friend, salon professional, or clinician. The payer is the one who pays, such as the user, a parent, a partner, or a household decision-maker. The replenisher is the person who restocks, often choosing the easiest way.

If you have ever wondered why some brands get early attention but struggle to keep customers coming back, this structure is often why. A brand might appeal to the user but not address the payer’s concerns. It might inspire people, but it doesn’t provide enough proof for influencers. Or it might create demand but make it hard to buy again.

The BPC Buying Unit (India)

Think of the process step by step: a trigger creates urgency, influence lowers the sense of risk, the payer checks for value and safety, the user tries the product, and the replenisher decides if buying again becomes a habit. This cycle is what really drives buying.

A “Small Shift” That Rewires Three Fundamentals

Switching from routine-based beauty to moment-based beauty seems like a small change, but it actually changes three key things: time, trust, and identity.

First, time collapses, and discovery moves closer.

In a moment-led world, the trigger and the cart can sit inside the same hour. “I have to look better tomorrow” produces a short path: content → search → validation → cart. Kantar’s “Beauty Spaces” idea explains why this is happening: when the job is immediate, work confidence, recovery after sweat, calm before sleep, people do not behave like long-cycle shoppers. They behave like problem-solvers.

For founders, this means your message should not just be detailed—it must also be easy to understand right away. Buyers need to know what your product does, who it is for, and when to use it, all within a few seconds.

Second, trust becomes part of the decision, and real proof matters more than just promises.

Moment-led buying does not lower standards. It raises them. When the purchase is tied to an outcome, acne, pigmentation, hairfall, or sensitivity, the buyer asks for evidence in the language they trust: reviews, before/after, ingredient clarity, and “people like me” validation. NielsenIQ’s India-focused beauty report explicitly points to growing demand for ingredient transparency and the increasing influence of digital discovery journeys in shaping what consumers trust and choose.

That is why many modern beauty brands focus on performance, even if they are for the mass market. Proof is not just a nice-to-have in marketing—it is essential for getting customers to buy. If you do not show proof early, you will lose customers and spend more to win them back.

Third, identity changes, and the same person can act as different types of buyers in a single week.

Consumers are not inconsistent, they just respond to different situations. Some days, they buy ‘safe and familiar’ products for restocking, when the risk is low. Other days, they choose ‘upgrade and impress’ items for social events. On another day, they might buy something to ‘fix a problem’ because they need results. The same person can switch between these needs in a week, so your brand is not just competing with one set of rivals, but with whatever fits the job at that time.

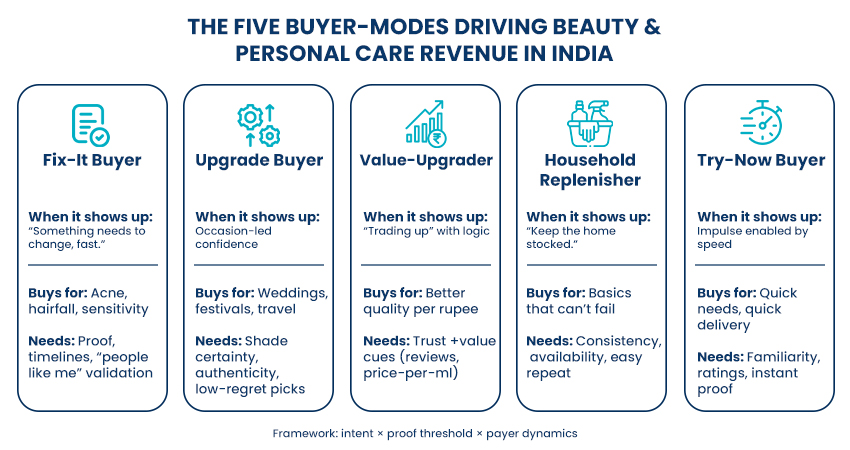

The Audience, Properly: Five Buyer-Modes That Move Revenue

Founders often divide the Indian market by age or city size. While this makes sense, it is not always the best way to plan products or keep customers. Looking at intent, the amount of proof needed, and who pays is often more useful. One household can have several types of buyers at once.

1) The Fix-It buyer: This buyer has specific problems like acne, pigmentation, hair fall, dandruff, odour, or sensitivity. They are not shopping for fun—they want to solve a problem and lower risk. The decision often involves several people: the user wants relief, influencers provide proof (like creator videos, reviews, or advice from clinicians), and the payer could be the buyer or a family member, especially for teens. Here, ingredient transparency and digital discovery are most important because trust comes from clear evidence.

2) The Upgrade buyer: This buyer appears during weddings, festivals, travel, gifting, and other social events. Proof is important, but confidence is even more so—they want authenticity, the right shade, premium packaging, and to feel sure their choice is safe. They like bundles, kits, and simple ‘complete the look’ ideas, because they are buying the version of themselves they want others to see.

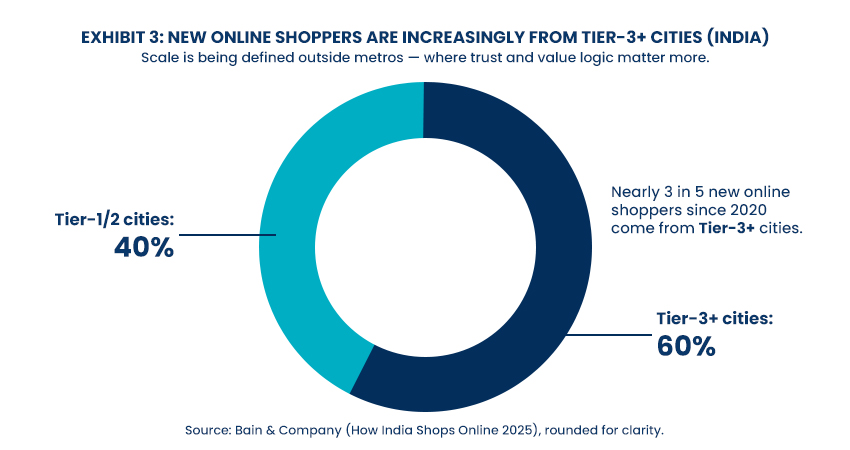

3) The Value-Upgrader: This buyer is neither ‘budget’ nor ‘luxury’—they know how to judge value. They will pay more if the upgrade makes sense, and they check reviews and compare prices carefully. Often, the payer or decision-maker in the household is more important, so brands need to sound trustworthy, not just trendy. This group is important because most new online shoppers in India since 2020 are from smaller cities.

4) The Household Replenisher: This person makes sure the household always has soaps, shampoos, basic skincare, and deodorants. They care most about reliability and availability. They are not looking for new things and are quick to notice disappointment. Many brands overlook how big this group is because it seems less exciting, but this is often where steady sales and repeat business come from

5) The Try-Now buyer: This is not about age or location, it is a behaviour driven by speed. When delivery times drop from days to minutes, people stop planning and start reacting. Discovery and buying happen simultaneously. The Try-Now buyer is influenced by ratings, familiar brands, and quick proof, and usually buys popular products rather than browsing the whole catalogue.

Channels Are Now Shaping the Buyer

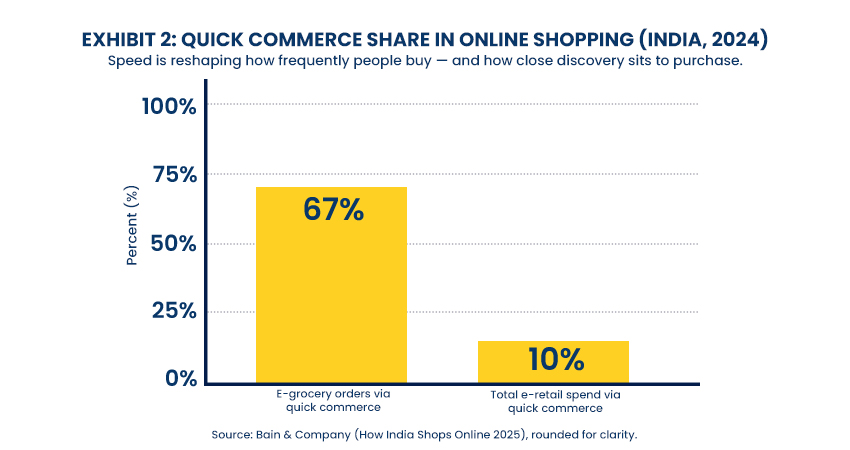

One way to look at channels is to see which role in the buying process they support. Some channels help people discover products, some help them feel confident in their choice, and some make it easy to buy again. In India, quick commerce has changed buying habits faster than any other form of commerce.

Bain’s 2025 report on India’s online shopping notes that in 2024, more than two-thirds of all e-grocery orders and about one-tenth of total e-retail spend happened on quick commerce platforms, and it expects rapid growth to continue through 2030.

Quick commerce share in online shopping (India, 2024)

Quick commerce is no longer niche.

This is important for beauty brands because quick commerce shortens the time from product desire to purchase. Brands with a clear main product, good availability, and easy-to-understand proof do well. It also means people restock more often, since buying again is now instant.

Offline shopping is still important, but for a different reason, it helps reduce risk in categories where people think carefully before buying. Trying products, finding the right shade, and making sure items are real all matter. Often, people discover products online, check reviews or visit a store to confirm, and then buy again through the fastest option.

Smaller-City Growth Is Not “Metro-Lite”; It Is a Different Decision System

With almost 60% of new online shoppers since 2020 coming from Tier-3 and smaller cities, the way people buy changes. Decision-makers in the household are often more important, and people look for clear, community-based proof. Once a product is trusted by the community, it spreads quickly through peer networks, but trust is the key to getting started.

Share of new online shoppers since 2020 from Tier-3+ cities (India)

For founders, the goal is not just to bring a metro brand to smaller towns, but also to ensure the payer and decision-maker understand the offer. Brands that clearly explain what they do, why they are safe, and how they fit into daily life will grow more smoothly than those that only focus on being new or different.

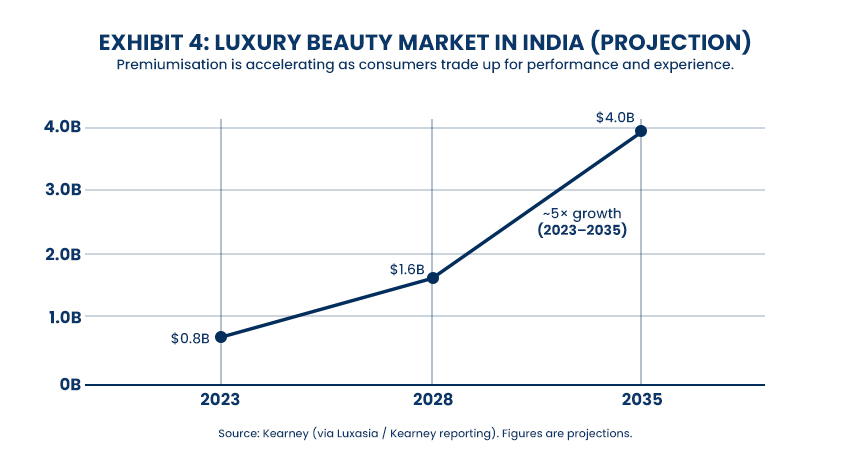

Premium Is Growing Because Outcomes and Aspirations Are Rising Together

India’s beauty and personal care market size varies by definition, with credible estimates ranging from the low-$20B range to the high-$20B range in recent years. What is more important than the market size is how it is growing. Premium products are not just about looking good anymore, they are also about delivering real results.

Kearney projects that India’s luxury beauty market could grow to $1.6B by 2028 and $4.0B by 2035.

Luxury beauty market in India (projection)

Even if you are not building a luxury brand, this growth matters because it sets a path for everyone. As people learn more about ingredients and get used to shopping online, they are willing to pay more for better results and experiences. Brands that know where they fit on this path and what proof they need to move up usually keep customers coming back.

What Founders in Any Category Can Borrow From This

Beauty is simply an early warning system for broader consumer behaviour. The same mechanics are increasingly visible in wellness, kids’ categories, food brands that rely on social discovery, and even certain B2B tools that are “used by one person but paid for by another.”

If you want a practical takeaway, it is this: you do not have one customer. You have a decision system. Growth becomes easier when you design for that system deliberately.

That starts with naming the roles in your category’s buying unit, then choosing the moments you want to own, then building a proof stack that speaks to the influencer and payer, and finally making replenishment effortless for the person who restocks.

When founders do this well, the category stops feeling chaotic. The buyer becomes predictable, because the behaviour has a structure.